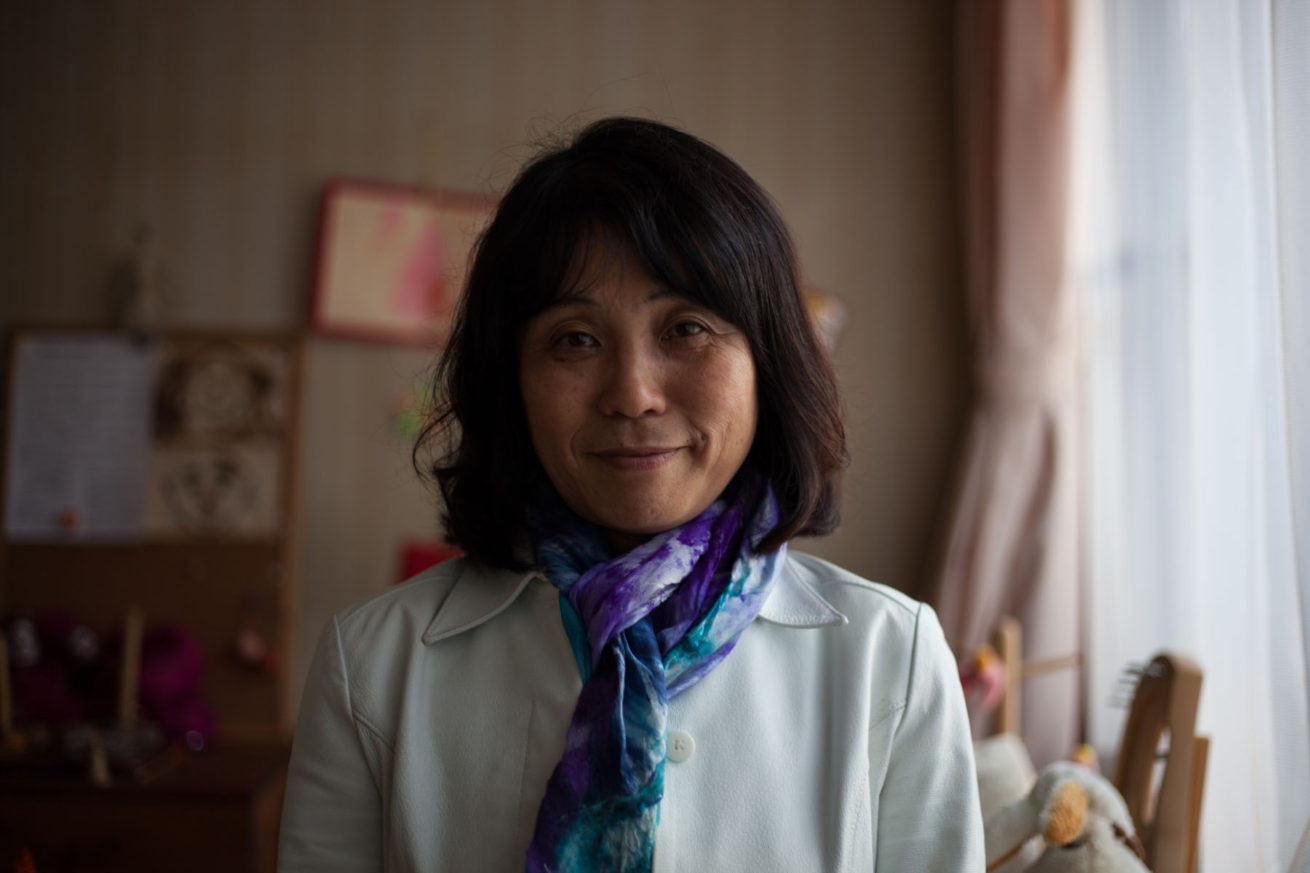

Sadako Monma

Soramame, Fukushima City

For two decades, Ms Sadako Monma has run a small nursery school, Soramame (meaning Beans), in Fukushima.

Following the Waldorf/Steiner philosophy, which emphasises imagination in learning and a focus on practical, hands-on activities and creative play for early childhood education; Ms Monma encouraged children to play outdoors in the fresh air, to touch the soil, and to otherwise connect with nature. This all changed after the meltdowns at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

In Watari, the school’s playground and the surrounding area was too contaminated for children to play safely. Despite the efforts of parents and the local community to decontaminate the school, and moving the school to another building closer to the road, the environment remained risky for children. After March 11, 2011, they spent most of their time at the school indoors.

“We started decontamination [of Soramame] earlier than the government decision. The areas we cleaned decreased radiation levels, but they rose again. Seeing this phenomena, one year later, I decided to move to another place.”

Many families left, and as children saw their friends leaving an uncomfortable atmosphere developed. Wanting to fix the situation but keep her business in Fukushima, for Fukushima children, Ms Monma decided to move to the outskirts of town where radiation levels were far lower.

When she did this, TEPCO cut her compensation payments to almost a quarter of what they were, saying that the number of children in Fukushima had now “recovered” (therefore her business should as well), but the reality for Soramame was quite different.

Before the meltdowns the school had 24 children. This dropped to seven in May 2011, and by 2012 only three remained. Light mapping inside and outside the new Soramame shows that contamination levels are indeed very low, especially compared to its previous location in Watari, which contains areas of elevated contamination to this day.

Before the meltdowns the school had 24 children. This dropped to seven in May 2011, and by 2012 only three remained. Light mapping inside and outside the new Soramame shows that contamination levels are indeed very low, especially compared to its previous location in Watari, which contains areas of elevated contamination to this day.

“Kids can’t understand the problem through language, so I struggled how to explain to them not to go close to the water drains etc. where radiation levels were higher than other areas – even after decontamination. I didn’t want to use the word “radiation” for kids, so I called it “bidibidi”, onomatopoeia. “There are bidibidi, so don’t cross to the corner of the playground. Bidibidi is like an electric shock that hurts you, but you can’t feel it.””

Moving the school to a new, safer location has not stopped the business suffering. At the new location in 2015, the school had four children every day, and a few others from time to time when their parents were busy. This is hardly the recovery TEPCO claims. While there may be families registered in Fukushima, many no longer actually live there.

Soramame’s initial struggle was with radioactive contamination, but its continued decline demonstrates the broader social and economics impacts of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. In the end, after five years struggling to get back to normal life, in 2016 Ms Monma has been left with no choice but to close her nursery and move on, 20 years after she first opened it.

More information on the project can be found here. All photos copyright Greenpeace/Greg McNevin.